Anovulatory cycles are a common concern for couples trying to conceive, being that, well, you can’t become pregnant if you aren’t ovulating, but anovulation can also be behind many issues that bother women not looking to plant belly fruit. Missed periods, long cycles, and spotting between periods can all call a lack of ovulation their cause. So, what causes anovulatory cycles? How can you tell if you have an anovulatory cycle? Are there symptoms? And more importantly, how can you start ovulating again?

What is an anovulatory cycle?

An anovulatory cycle is one where you don’t ovulate.

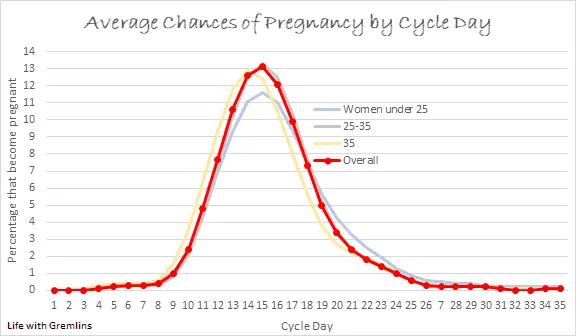

Ovulation, or the release of an egg from your ovary, normally occurs around mid-cycle. To determine when “mid-cycle” is for you, take your cycle average (the average number of days between the first day of your period and the start of your next period) and divide it by two. For example, if you run a 28-day cycle on average, you probably should ovulate around 14 days after the first day of your period. You can read a more in-depth guide on pin-pointing ovulation here. This may also help you determine if you are ovulating. Note that the presence of a period doesn’t guarantee ovulation.

What causes anovulation?

Almost all causes of anovulation boil down to the same root cause, hormonal imbalance. It’s what’s causing that hormonal imbalance that varies.

To help you better understand the explanation of some causes of anovulation listed below, let’s take a moment to review fertility hormones.

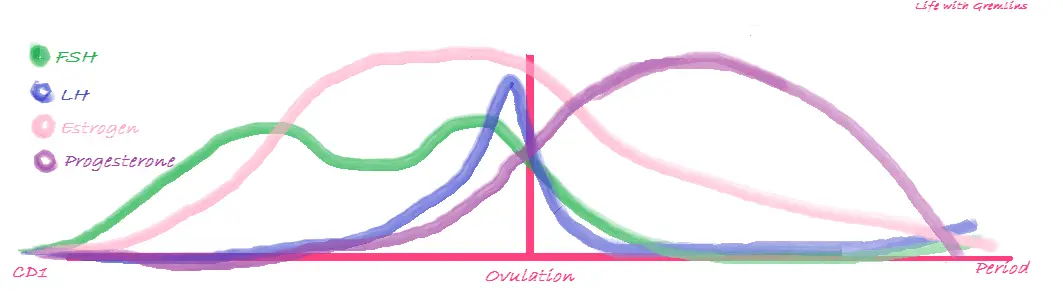

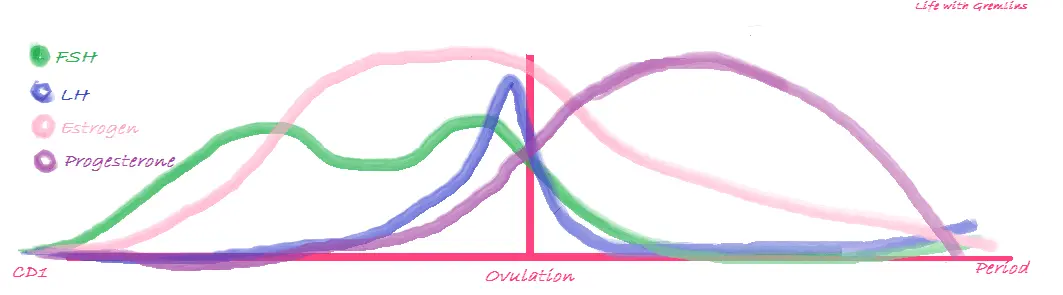

The first hormone involved in ovulation is gonadotropin releasing hormone (GnRH) secreted by the hypothalamus. This hormone cues the pituitary gland to produce follicle stimulating hormone (FSH).

FSH causes a follicle to develop creating a mature egg for ovulation. This development signals the production of estrogen to build your uterine lining for implantation.

Estrogen’s rise triggers the pituitary to increase the release of luteinizing hormone (LH). LH is the hormone that prompts your ovary to release an egg.

After ovulation, the structure left behind by the egg’s exit begins to produce progesterone. Progesterone maintains your uterine lining for a potential pregnancy.

As you can see, the hormones of ovulation are much like dominos, each triggering an effect in the other. This is why an imbalance somewhere in the chain is so likely to cause anovulation. Any condition that alters these hormones, hormones that can affect these hormones, or the structures that release these hormones can then lead to anovulatory cycles.

Common culprits of anovulation include:

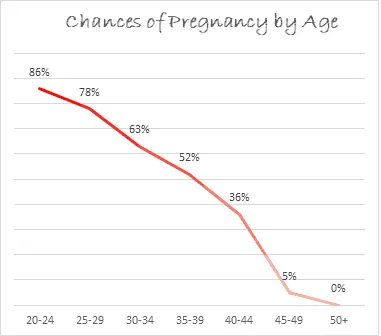

Age: Anovulatory cycles are considered normal in women under 19 and over 35.

This is because both timeframes typically include natural hormonal flux as a result of the start of menstruation, and later, the start of menopause. The closer you are to either of these events the higher the chance of anovulatory cycles. For instance, a teen who only began menstruating the following year is more likely to see anovulation than an older teen whose cycle began years prior. A 40-year-old is more likely to see anovulation than a 35-year-old (unless she has a familial history of early menopause).

Ovarian reserve: A lack of eggs can lead to irregular ovulation or anovulation.

The number of eggs available to ovulate throughout your life is set before birth, and as time passes, that number diminishes. While more common in older women (and often the cause of those before-mentioned hormonal shifts in women over 35), low ovarian reserve can affect younger women. In some cases, the cause is unknown, though genetic abnormalities, adrenal conditions, cancer treatments, ovarian surgeries, and earlier excessive fertility drug use can all be factors. High FSH is often a tell-tale sign.

Body fat percentage: Having a BMI below 18.5 or above 25 can increase your risk of anovulation.

High body fat: Estrogen is produced by your ovaries but can also be produced in fat cells. Excess fat cells then can lead to excess estrogen. Excess estrogen will suppress FSH and LH production (this is why hormonal birth control contains synthetic estrogen). Estrogen imbalance also tends to push other key-fertility hormones out of balance, such as progesterone.

Low body fat: While low body fat has been shown to cause anovulation more frequently than high body fat, the mechanism is not fully understood. There are two common theories. One being that body fat is essential to sufficient estrogen production, and the other being an evolutionary reaction to stress. It’s likely both are a factor.

Excessive exercise, dieting/low caloric intake, and/or stress:

In addition to low body fat, any activity that causes the body to react with the release of stress hormones, such as cortisol, can suppress the pulsation of GnRH. As GnRH prompts the production of FSH at the beginning of the menstrual cycle, this can then halt ovulation.

Hyperprolactinemia:

Hyperprolactinemia is a condition of high prolactin, a hormone that aids in the production of breast milk, that can diminish LH and FSH secretion. It’s most commonly caused by small pituitary tumors. Women with hyperprolactinemia may also see nipple discharge outside of breastfeeding.

Hyperthyroidism/Hypothyroidism: Both an over or under-active thyroid can lead to a lack of ovulation. In hyperthyroidism, it’s believed sensitivity to GnRH is increased leading to higher than normal levels of LH, FSH, and estrogen. In hypothyroidism, prolactin levels are elevated, which reduces LH and FSH secretion.

PCOS: Polycystic ovarian syndrome accounts for around 70 percent of chronic anovulation cases under the age of 35 making it by large the most common cause of anovulation in that age group. In patients with PCOS it’s believed excessive androgen production overstimulates the ovaries leading to the maturation of multiple follicles developing eggs. In many cases, none of the eggs mature fully, ovulation doesn’t occur, and multiple cysts form on the ovary (polycystic=many cysts). These cysts further prevent ovulation in the future. Common symptoms of PCOS include high body fat with difficulty losing weight, excess body hair growth (often dark), head hair loss, cystic acne, and irregular/absent periods.

Breastfeeding: As prolactin is necessary for lactation, breastfeeding will cause high levels, which as stated above suppresses LH and FSH secretion.

While the causes above are the most commonly seen, this is not an all-inclusive list. If you suspect you may not be ovulating your care provider is the best person to evaluate your condition. Certain medications may also cease ovulation.

How common is anovulation?

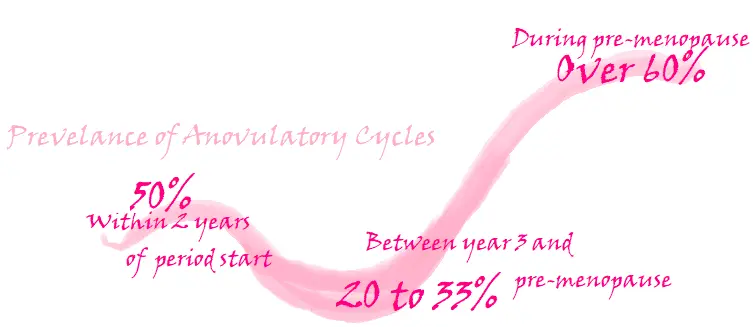

The prevalence of anovulatory cycles varies by life stage. Note that these ranges are not given by age, as the age women hit these stages also varies. They also apply to a general sampling of women, those with a condition known to increase the risk of anovulatory cycles, such as PCOS, would see higher rates or even chronic anovulation.

In the first 2 years after menstruation begins: 50 percent of all cycles are anovulatory.

Between the second year and pre-menopause: 20 to 33 percent of all cycles are anovulatory.

Pre-menopause (periods have not stopped): 60+ percent of all cycles are anovulatory.

How can you tell if you have an anovulatory cycle?

Anovulation Symptoms:

Anovulation is the most common causes of a missed period outside of pregnancy making a missed period one of the most common symptoms of anovulation. Other common symptoms include:

-Irregular bleeding/periods (variance more than 3 days in cycle lengths)

-Spotting between periods

-A lack of typical side effects of high progesterone known as PMS (sore breasts, water-weight gain, irritability, etc.)

There may also be a lack of typical ovulation symptoms such as clear-stretchy cervical mucus around mid-cycle. However, as high estrogen is common in many of the underlying causes of anovulation, and estrogen increases vaginal discharge, this may be less noticeable.

Anovulation with regular periods: Note that while missed or irregular periods are common with anovulation, it is possible to have regular periods without ovulating. This is also known as silent anovulation. In this case, the anovulatory cycles are usually sporadic (not occurring every cycle) rather than chronic.

Anovulatory bleeding vs periods: Knowing that one can have regular period-like bleeding and not ovulate poses and important question, is there a way to tell the difference? Unfortunately, the answer is no. The only difference between anovulatory bleeding and a period is an egg is not shed in an anovulatory bleed. This is not something you can see simply from flow, color, etc.

BBT charts: Basal body temperature can be one way to confirm anovulatory cycles even with regular bleeding. After ovulation the rise of progesterone creates a noticeable temperature shift. If this shift is absent, ovulation is unlikely to have occurred. You can read more about how to chart BBT here.

Anovulatory cycle or pregnant: On the other side of the spectrum, since anovulation frequently causes missed periods (which are actually just very long cycles), how can you tell if you’re pregnant or experiencing anovulation? A pregnancy test is the easiest answer. If your test is negative, and you haven’t had a period in the last 90 days (amenorrhea), it’s best to see your care provider for further testing. Please note that symptoms are not a reliable method of telling anovulation from pregnancy. Both involve hormonal imbalance and can present with similar symptoms.

How are anovulatory cycles treated?

Sporadic anovulation usually requires no treatment and is considered normal. Chronic anovulation is treated by addressing the underlying cause excluding cases where age is the culprit (nothing can be done for age-related anovulation). Often this includes dietary and lifestyle changes aimed at normalizing weight and medications which may induce ovulation, balance a particular hormone, or treat a condition.