As if pregnancy and labor aren’t confusing enough, doctors, midwives, and even other mothers seem to insist on using terminology many first-time mothers have no clue what means. Dilated? Softened? +1, 2, or 3? What does all this mean? This article will look at many pregnancy and labor-related terms and explain their meaning in common language. Most of the terms you likely won’t know what mean during your pregnancy will begin to pop up in the third trimester as your body prepares for labor or may not be mentioned until during your labor.

Dilation:

Dilation is a term you may hear towards the end of your pregnancy. This term is in regard to your cervix. Your cervix is a tube-like structure connecting your vaginal canal and your uterus where your baby is. Your baby will pass through your cervix during delivery. As labor approaches, your cervix begins to open preparing to allow your baby out. Dilation refers to how open your cervix has become. This term will be used in conjuncture with a number in cm. For instance, your doctor may say, “You are 2 cm dilated.” This means that your cervix is open 2 cm or about two fingers in width. For reference, when you are in the final stages of your labor and begin to push your cervix will be open or dilated to 10 cm.

Effacement:

Effacement is a sister term to dilation that is also in regard to your cervix. As your cervix opens, it will also thin and become shorter. Your doctor may say something like, “You are 1 cm dilated and 20 percent effaced.” This would mean your cervix is open one cm, or around one finger’s width, and has thinned 20 percent of its original size. Before your baby is delivered your cervix will efface to 100 percent making it paper-thin.

Soft/Hard Cervix:

While these may be words you have heard before, they have a different meaning when your doctor says them. This is yet another term in reference to the condition of your cervix. While your cervix dilates and thins it also becomes softer because of these changes. Your doctor saying your cervix is firm or hard would simply mean it has not begun to change. If your doctor says your cervix is soft, it means it has begun to prepare for labor.

Engaged/Lightening:

The term engagement or lightening of your baby means that he or she has dropped further into your pelvis in preparation for delivery. This usually occurs in the last few weeks of your pregnancy. You may notice you breathe easier or your belly changed shape.

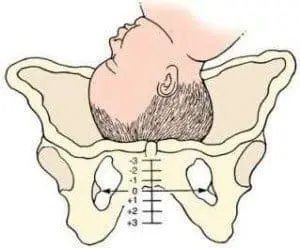

Station:

(+1, -2, 0, etc.): This term is usually used in conjunction with the term engaged or lightening. Station refers to your baby’s position in your womb in reference to two bony spines on your pelvis and can vary from a +3 to a -3. A -3, -2, or -1 station means that your baby has not yet dropped into your pelvis or engaged and is 3-1 cm above the bony spurs in your pelvis depending on the corresponding number. 0 Station means that the baby is level with the bone spurs and has dropped. +3, +2, or +1 mean the baby is 3-1 cm below the bony spurs in your pelvis. Positive stations indicate a move towards the cervix and usually mean labor is imminent.

So to combine this term with other terminology it regularly is used with, you may hear something like this in the final week of your pregnancy, “You are soft 2 cm dilated, 45 percent effaced and your baby is at -1”. This means your cervix is soft or ready for labor, open 2 cms, thinned 45 percent of its original size and your baby is 1 cm above the bones in your pelvis. All of this information is an attempt to estimate when labor will occur. While being very dilated, effaced, and soft with a zero station is a pretty good indication labor is near, it’s not a guarantee.

Posterior/Anterior:

These terms refer to the way the baby is facing. This isn’t particularly important until during your labor. Posterior means that the baby is facing up with the back of its head against your spine or posterior region, rather than anterior or facing down with the back of the head against your tummy. In a normal labor, a baby faces down making it easier to pass through the birth canal. A baby that is facing posterior can be delivered but may increase the risk of c-section and will result in more back pain for you during delivery.

Breech Position:

Breech position is another term used to describe the position your baby is in. The ideal position for a baby to be in at the time of labor is called vertex position meaning the baby is head down in the uterus. Breech position or breech means that the baby is feet or butt down rather than head down. When the feet are down and one or both feet will exit the cervix first this is called a footling breech. When the butt is down, but the feet and legs are folded up by the head this is called a frank breech, and finally, if the butt and feet are down in almost a kneeling position this is called complete breech. A breech delivery of any kind does not necessarily mean a c-section will be needed, but it does increase the chance dramatically. Most healthcare providers will try to turn a baby that is in a breech position when labor approaches.

Traverse Position:

Traverse position, which may just be called traverse, means that the baby is laying sideways or shoulder/arm down towards the cervix. Sadly, traverse-positioned babies almost always result in a c-section if they can’t be turned before labor begins.

Crowning:

Finally, crowning, crowing, or crowned means your baby’s head is visible to your doctor outside of your vagina during delivery. This means the baby is almost out, and you’re almost done.

While there are certainly more terms you may hear during your pregnancy and labor these are the most common and the most misunderstood terminologies. Hopefully, this article has left you feeling more in the loop.